Scripps Oceanography Research pegs ID of red tide killer

Related images

(click to enlarge)

Researchers at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego have identified a potential “red tide killer.” Red tides and related phenomena in which microscopic algae accumulate rapidly in dense concentrations have been on the rise in recent years, causing hundreds of millions of dollars in worldwide losses to fisheries and beach tourism activities. Despite their wide-ranging impacts, such phenomena, more broadly referred to as “harmful algal blooms,” remain unpredictable in not only where they appear, but how long they persist. New research at Scripps has identified a little-understood but common marine microbe as a red tide killer, and implicates the microbe in the termination of a red tide in Southern California waters in the summer of 2005.

While not all algal outbreaks are harmful, some blooms carry toxins that have been known to threaten marine ecosystems and even kill marine mammals, fish and birds.

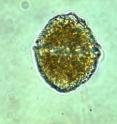

Using a series of new approaches, Scripps Oceanography’s Xavier Mayali investigated the inner workings of a bloom of dinoflagellates, single-celled plankton, known by the species name Lingulodinium polyedrum. The techniques revealed that so-called Roseobacter-Clade Affiliated (“RCA cluster”) bacteria—several at a time—attacked individual dinoflagellate by attaching directly to the plankton’s cells, slowing their swimming speed and eventually killing them.

Using DNA evidence, Mayali matched the identity of the RCA bacterium in records of algal blooms around the world.

In fact, it turns out that RCA bacteria are present in temperate and polar waters worldwide. Mayali’s novel way of cultivating these organisms has now opened up a new world of inquiry to understand the ecological roles of these organisms. The first outcome of this achievement is the recognition of the bacterium’s potential in killing red-tide organisms.

“It’s possible that bacteria of this type play an important role in terminating algal blooms and regulating algal bloom dynamics in temperate marine waters all over the world,” said Mayali.

The research study, which was coauthored by Scripps Professors Peter Franks and Farooq Azam, is published in the May 1 edition of the journal Applied and Environmental Microbiology.

“Our understanding of harmful algal blooms and red tides has been fairly primitive. For the most part we don’t know how they start, for example,” said Franks, a professor of biological oceanography in the Integrative Oceanography Division at Scripps. “From a practical point of view, if these RCA bacteria really do kill dinoflagellates and potentially other harmful algae that form dense blooms, down the road there may be a possibility of using them to mitigate their harmful effects.”

The researchers based their results on experiments conducted with samples of a red tide collected off the Scripps Pier in 2005. Because RCA bacteria will not grow under traditional laboratory methods, Mayali developed his own techniques for identifying and tracking RCA through highly delicate “micromanipulation” processes involving washing and testing individual cells of Lingulodinium. He used molecular fluorescent tags to follow the bacteria’s numbers, eventually matching its DNA signature and sealing its identity.

“The work in the laboratory showed that the bacterium has to attach directly to the dinoflagellate to kill it,” said Mayali, “and we found similar dynamics in the natural bloom.”

Franks said he found it a bizarre concept of scale that Lingulodinium dinoflagellates, which at 25 to 30 microns in diameter are known to swim through the ocean with long flagella, or appendages, are attacked by bacteria that are about one micron in size and can’t swim.

“It’s somewhat shocking to think of something like three chipmunks attaching themselves to an elephant and taking it down,” said Franks.

While the RCA cluster’s role in the marine ecosystem is not known, Azam, a distinguished professor of marine microbiology in the Marine Biology Research Division at Scripps, said harmful algal blooms are an important problem and consideration must be given to the fact that red tide dinoflagellates don’t exist in isolation of other parts of the marine food web. Bacteria and other parts of the “microbial loop” feed on the organic matter released by the dinoflagellates and in turn the dinoflagellates are known to feed on other cells (including bacteria) when their nutrients run out.

Dinoflagellate interactions with highly abundant and genetically diverse bacteria in the sea have the potential to both enhance and suppress bloom intensity—but this important subject is only beginning to be explored.

“The newly identified role of RCA cluster is a good illustration of the need to understand the multifarious mechanisms by which microbes influence the functioning of the marine ecosystems,” Azam said.

“This type of discovery is helping us understand algal bloom dynamics and the interactions among the components of planktonic ecosystems in ways that we’d imagined but previously lacked evidence,” said Franks.

Source: University of California - San Diego

Other sources

- Red Tide Killer Identifiedfrom Science BlogFri, 2 May 2008, 22:21:05 UTC

- Red Tide Killer Identified: Bacteria Gang Up On Algae, Quashing Red Tide Bloomsfrom Science DailyThu, 1 May 2008, 18:28:10 UTC

- Scripps Oceanography Research pegs ID of red tide killerfrom PhysorgThu, 1 May 2008, 16:56:07 UTC

- Oceanography Research Pegs ID of Red Tide Killerfrom Newswise - ScinewsThu, 1 May 2008, 16:28:07 UTC