Fruit flies soar as lab model, drug screen for the deadliest of human brain cancers

Related images

(click to enlarge)

Fruit flies and humans share most of their genes, including 70 percent of all known human disease genes. Taking advantage of this remarkable evolutionary conservation, researchers at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies transformed the fruit fly into a laboratory model for an innovative study of gliomas, the most common malignant brain tumors. "Gliomas are a devastating disease but we still know very little about the underlying disease process," explains John B. Thomas, Ph.D., a professor in the Molecular Neurobiology Laboratory and senior author of the study, which is published in the current edition of the Public Library of Science Genetics. "We can now use the power of Drosophila genetics to uncover genes that drive these tumors and identify novel therapeutic targets, which will speed up the development of effective drugs."

Better models for research into human gliomas are urgently needed. Last year alone, about 21,000 people in this country were diagnosed with brain and nervous system cancers, Senator Edward M. Kennedy the most famous among them. About 77 percent of malignant brain tumors are gliomas and their prognosis is usually bleak. While they rarely spread to elsewhere in the body, cancerous glial cells quickly infiltrate the brain and grow rapidly, which renders them largely incurable even with current therapies.

Gliomas originate in brain cells known as "glia" and are categorized into subtypes based on how aggressive they appear, with glioblastoma being the most common and most aggressive form of glioma. Their diversity is mirrored by the number of different signaling pathways involved in the generation of these tumors, yet aggressive gliomas all seem to have one thing in common: Most, if not all human glioblastomas carry mutations that activate the EGFR-Ras and PI-3K signaling pathways. Such mutations are also thought to play a key role in developing drug resistance.

"Fruit flies possess homologs of many relevant human genes including EGFR, Ras, and PI-3K," explains postdoctoral researcher and first author Renee Read, who spearheaded the project. "We developed the Drosophila model to figure out how these genes specifically regulate brain tumor pathogenesis and to discover new ways to attack these tumors."

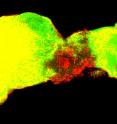

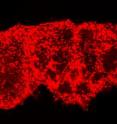

When Read activated both signaling pathways specifically in glia in genetically engineered fruit flies, she found that, just as in the mammalian brain, activation of the EGFR-Ras and PI-3K pathways gave rise to rapidly dividing, invasive cells that created tumor-like growths in the fly brain, mimicking the human disease.

"Once I had verified that the fly tumors share key aspects with human gliomas, I could use the model to screen for new genes that are involved in disease process and compare them to the genes that were found as part of The Cancer Genome Atlas' glioblastoma initiative," explains Read.

Glioblastoma is one of the first cancers studied by The Cancer Genome Atlas research network, whose goal is to accelerate understanding of the molecular basis of cancer through the application of modern genome characterization technologies such as large-scale genome sequencing.

Like most cancers, gliomas arise from changes in a person's DNA that accumulate over a lifetime but sorting changes with wide-ranging impacts from innocent bystanders has been a challenge. "While these initiatives give us big lists of altered genes they don't tell us much about which ones are really important," says Read. "Addressing this question in mouse models or patient studies is extremely expensive and time-consuming. In flies, I can test hundreds of genes every week."

The Salk researchers are now using their fly model to search for genes and drugs that might block EGFR/PI-3K-associated brain tumors. The drug tests are being done in collaboration with co-authors professor Webster Cavenee, Ph.D., and associate professor Frank Furnari, Ph.D., both experts in human brain tumor biology at the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research at the University of California, San Diego.

The researchers are hoping that through their combined efforts new discoveries from the fly model can be rapidly translated into mouse and human brain tumor studies and lead to development of new therapies for this deadly cancer.

Source: Salk Institute

Other sources

- Fruit flies soar as lab model, drug screen for the deadliest of human brain cancersfrom PhysorgFri, 13 Feb 2009, 14:07:30 UTC

- Fruit Flies Soar as Lab Model, Drug Screen for the Deadliest of Human Brain Cancersfrom Newswise - ScinewsFri, 13 Feb 2009, 1:35:22 UTC